Incidentally, I have not mentioned anything on this blog about the major architectural exhibition that I worked on early this year: When is Space? - that which was curated by Rupali Gupte and Prasad Shetty, commissioned by Pooja Sood, held at Jawahar Kala Kendra. The exhibition took place during 21st January to 21st April 2018. The reason why nothing came to this blog is because I put together an entire separate website for the event (www.whenisspace.in). I contributed several writing pieces on the whenisspace blog. Besides, as the Assistant Curator, my responsibility was to put together the exhibition catalogue, the exhibition placards, overseeing the content and design and lastly conducting the seminars and conferences as allied events. Alongside, I was also made responsible for putting together what came to be called as the 'Jaipur Room' - the one with all historical documents of the city. Often it becomes very difficult to ascertain what one's role has been in putting up an exhibition when working in a creative group. Several of our energies went together in creating many parts of the exhibition. My effort was to become a lubricant which could help mobilize the entire exhibition towards its completion.

|

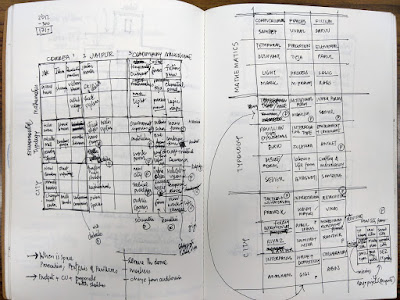

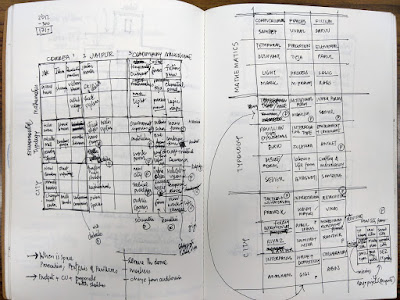

| Prasad's pre-planning for the exhibition layout. |

|

| Pankaj Sharma with the Curatorial Team, on Jaipur Archives |

|

| Jaipur Winters with the team |

The curators involved me generously over the entire planning - taking me together for site visits, studies and archives. I have to commend Rupali and Prasad for their persistence and hard work with which they envisioned ideas into reality. I feel too insignificant of my contribution within the entire process as compared to their work. I merely tried to "fill in" where some directorial purpose was required as they focused on other more important things. This was more circumstantial than intended, for I was quite occupied assisting Riyas Komu for Serendipity Arts Festival's 'Young Subcontinent' Project in Goa. There was substantial traveling and research involved along with significant amount of coordination that went into bringing and installing artists from across six countries of South Asia for the Young Subcontinent Project. Within this, there was my teaching at SEA along with visits to Jaipur. It was useful to be informed about the developments in person, however, my initial involvement began from refining the curatorial note and then working on the graphic material for the exhibition, eventually robustly taken over by our project assistant Dhruv Chavan.

Pooja Sood, unknowingly, although perhaps rightfully qualified 'When is Space?' as one of the largest exhibitions of architecture in India. While one had preliminary doubts, one was compelled to believe in her pre-assessment on seeing the works manifest on ground. Which other architecture exhibition brought five live installations, life size scaled models, room full installations and a range of drawings and models together in once space? In addition, the exhibition also boasted of two conferences along with a dozen curatorial walks. Such an ambition clearly brings the scale of the exhibition at par with either Vistara, or The State of Architecture. The project almost became a mini-biennale. Originally intended to run for three months, it was extended by another month.

One of my biggest learnings was in the process of translation of the text in Hindi. The work opened me up to some really exciting conversation with our translator Sveta Sarda, and led me to the undertaking of my next important class project on translating the wonderful catalogue of Vistara exhibition (one that was curated by Charles Correa) as a part of my History class. As a translator / editor, one is constantly struggling between what essence to retain, and what to let go. It also opened me up to the rich internal contemplation on the idea of space as conceived in oriental philosophy.

To just shift behind the scenes, Prasad, since much beginning prefaced four ideas on space (something I think he learnt from Lefebvre's 'The Production of Space'). It is important that they are noted down for architectural consideration, and to remind oneself that architects play a role in steering the discourse on space. These four propositions, observed by Prasad from his research on understanding of space include four categories in which it has been understood and intervened so far:

a.

Euclidean space: The mathematical understanding of space, through geometry and eventually cartography - taken ahead through endavours of Newton and Descartes in order to locate objects in reality. In essence, they imagined space as a container for events in life.

b.

Einsteinian space: Einstein worked through folding space and time (and everything within it) into a continuum, indicating that we are aggregates of time and space. In some ways, it is an empirical extension of spiritual teachings of vedas. His famous mathematical equation E=mc2 also brings together life as energy that is constituted of light and matter.

c.

The Kantian Space: Kant suggests that 'space' is something like a lens that one wears to see things (in a most basic manner). He suggested that human beings are born with certain 'apriori' idea of space and time.

d.

Lefebvre's space: Lefebvre believed that space is a cultural phenomenon, and that it is produced through the constant act of social process. Thus, for Lefebvre, space was a social entity.

On reflection, one finds three important guiding principles that came to structure the exhibition. Incidentally, these were also points that I had raised in my critique of 'The State of Architecture' exhibition held at NGMA in Mumbai during 2016. These include:

1. The Idea of Practice (and not projects): The 'When is Space?' exhibition attempted to focus on the ongoing inquiries that individual architects are pursuing within their practices. The projects included in the exhibition were seen merely as sharp pointers that exemplified these questions. Thus, projects do not become an end in themselves for a practice, rather another opportunity to experiment with the ongoing questions that it tries to engage in over a longer term. The exhibition was thus, not a collection of architectural projects, rather a bringing together of contemporary inquiries on space hidden/latent within the architectural practices across the country.

2. The question of Space: Everyone on the team worked with the understanding that space is a

produced act. It is not a default "given". The curatorial endavour attempted to provoke and ask the question of space as a historical condition - what it is, and what it means today. It thus did not differentiate between architects, artists, philosophers, intellectuals, theorists, students, and many other 'practitioners of space'. Thus, architecture was located within an expanded field, and the question of space was central to the curation. The exhibition asserted that space is a shared entity, and it is co-produced, where architects play the role of sharpening its ideological dimension. It is here that the exhibition also attempts to address the "when". People and space produce each other through a series of engagements, and certain configurations of space characterise key moments in time. The exhibition attempted to ask what regimes of thinking 'space' have existed, and how does one locate contemporary architectural practice within it?

3. The Paradox of Exhibiting Architecture: What methods does one employ to exhibit an entity that encompasses our very lives? The exhibition experimented and brought together a range of ways in which architecture gets experienced - through drawings, models, installations, mockups as well as the virtual. Further, it brought audiences to consider intangible elements like light as well as sound (music and spoken word) structure our experiences in a given space. The exhibition pushed people to create their own associations by throwing them into a gamut of carefully curated sensorial environments, punctured by historical and contemporary readings. In doing so, it provoked the viewers to think how life shapes up through sensorial interaction and consumption; how we become inhabitants of the world, and what, after all, is the nature in which we inhabit the world today?

--

Some memories:

|

Planning Spatial Toys. Drawing by Dhruv Chavan under the direction of Milind Mahale.

|

|

| Making frames for hanging the mounted photographs |

|

| Teja Gavankar's installation in process |

|

| The meticulous planning behind the House of Five Gardens by Samir Raut. |

|

| Vipul Verma working the construction of the endless cloth pieces in order to create a large enclosure within the volume of JKK, for Sameep Padora's installation |

|

| Bringing the tallest staircase on campus! |

|

| Reams of cloth... |

|

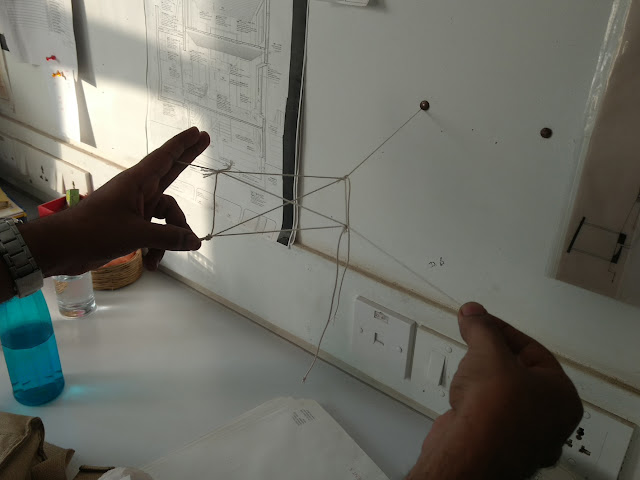

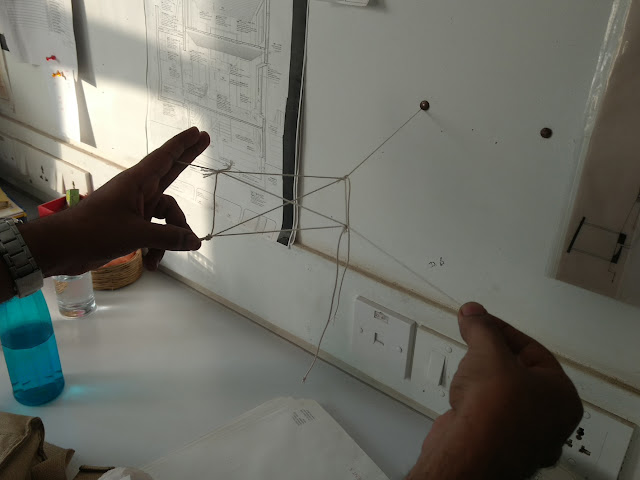

The first iteration of the Floating Roof, by Dushyant Asher, held over his work desk at the School of Environment & Architecture

|

Please visit www.whenisspace.in for more information!