Monday, January 14, 2019

Sunday, December 16, 2018

Young Subcontinent 2018

Through the last two editions, the Young Subcontinent project attempted to chart the contours and sightlines of South Asian art imagination and art practice, illustrating and celebrating the lines of convergence, the commonalities in historical experiences, the entanglements of its cultural roots, and most crucially, its shared aspirations and dreams. These tapestries of art practices from across the continent meditated upon and mediated the complex social, religious and political spheres of life in the Subcontinent. While, the first edition triggered dialogue and exchange between the artists from the region, the second edition probed further the socio-cultural and political tensions and struggles that animate and also in many ways, restrict imagination and art-making in the region. YS opened up contemporary aesthetic parallels to the much-trodden trade routes of yore, tracing common lineages of art history and practices, shared traditions of faith and ideas and ideologies of the sacred and the secular. The experiences of sharing a common space/platform at YS and the exchanges it provoked and pursued, brought to the surface the need to reinvent and reassert vital connections and traditions of exchange, to strengthen arts infrastructure and the urgency of developing vibrant platforms for intercultural dialogues and synergies. These interfaces invariably pointed to the potential of art in excavation and celebration, assertion and redirection of tools and techniques, resources and efforts towards rediscovering and reasserting the cosmopolitan roots and global imagination of the region. In the present global art, economic, and political context, such articulation of creative discourses and fresh sightlines are essential to foresee and forge new, exciting common futures through art-making, art-thinking and art-organising.

The geopolitical dynamics of South Asia is subject to several local, regional, national and global factors. On the one side is a kind of globalisation imagined and imposed by capital, aggressively moulding the structure and direction of economics and politics of nation states in the region. On the other are the menacing forces of fundamentalism and totalitarianism that threaten the democratic fabric and ways of living in this region. So an art project like YS is necessarily a struggle against monolithic culturalism and narrow nationalism based on othering, and one that argues vehemently for the coexistence and celebration of pluralities that constitute South Asia, its societies, identities, politics, economy and culture.

With this in view, the YS project ought now expand points of contact, explore sightlines of common struggles and aspirations, look at reassertion and reinvention of geographies, facilitate conversations and narratives of peaceful coexistence and democratic aspirations. YS aspires to imagine and develop into a free platform of art-making and theorizing, storytelling and mentoring, that will draw, and draw from, new sightlines for inter-cultural and political diplomacy.

Monday, December 10, 2018

Under Construction // 2018

an exhibition curated by Anuj Daga

5th to 10th December 2018

Delhi.

Landscapes of construction have become common sites of encounter within everyday life in South Asian cities. Infrastructural expansions, large scale housing and institutional projects along with repairs and redevelopments seem to perpetually churn people within the flux of construction activity. On the one hand, the manoeuvring of construction sites plead for us to deal with blockages, dangers, risks, inconveniences and diversions thereby demanding in us a slowness to labour the growing city; and on the other hand, they infuse amazement and amusement in our everyday routine. Thus, contemporary urban life in South Asia inevitably gets produced within the poetics and politics of construction. In perpetual making, its cities allude to ruins, waiting to be completed, suspending us in an uneven field of promise and hope. Bodies and desires remain as incomplete as our built environment. Life and action intuitively begin to articulate form and intent in the tension of the finished and the unfinished.

How and what do people negotiate with and draw from constructions around them in their everyday? What new relationships get forged in living through the cumbersome, irritant, yet hopeful environments of sites under construction? How does construction aesthetic inform everyday life and thinking? How does growing up in a landscape of construction shape and feed into cultural production of a place and people? This project brings together seven artists / architects whose works draw from sites under construction, or who strategise its logic to open up new readings and relationships with the ever changing environment. In the process, they attempt to open up a discourse on the aesthetics and politics of construction.

Under Construction may offer an appropriate positioning for South Asian cities as a place of longing and hope but more so as one that invents new forms of life within the process of becoming. New vantages are extended to us in diversions and new places are formed in the crevices of inconvenience. In their journeys of making, objects and spaces carry a multiplicity of dispositions that may hold immense possibilities of adapting and intervening into emerging urban dynamics. Construction sites offer rich metaphors in order to understand life and work as an ongoing practice. They shift our attention from products to processes, from objects to tools and from solutions to possibilities, which may allow us insights into new geometries of speculation.

participating artists: Avijit Mukul Kishore, Karthik Dondeti, Nisha Nair-Gupta, Poonam Jain, Pratap Morey, Ritesh Uttamchandani, Shreyank Khemalapure

Here is a link to the catalog:

Curatorial Intensive South Asia Brochure

Images from the exhibition:

Under Construction

Seven artists / architects draw ideas inviting us to engage in the poetics and politics of living that reveals in the manoeuvring of construction sites around them - those that demand in us a slowness to labour the growing city on the one hand; and infuse amazement and amusement in our everyday routine on the other.

5th - 10th December, 2018, Khirkee Studio, S-4, Khirkee Extension, New Delhi - 110017

Avijit Mukul Kishore

The Concrete Lift

HD video, colour

28 minutes, loop

2018

Avijit Mukul Kishore has been filming the changing landscape around the building that he lives in, from the windows of his eleventh floor apartment, for several years. He lives in the suburb of Borivali East in Bombay, which used to be an industrial area. With the very visible de-industrialisation of the city due to real-estate pressures, the landscape of this area began to change rapidly. The industrial landscapes were vast and largely low-rise. These are replaced by high-rise residential buildings which at present are around thirty storeys high.

The video presented looks at this changing landscape and scale - both of the city and the human body. The TATA Steel Wire Division factory, an important landmark in Borivali, was demolished after its operations shifted to a new site outside the city. In its place and all around came up residential buildings. These were built with the slow and systematic labour of young migrant workers, many of them in their teens. One sees in the film, how these workers toil through heavy rain and sun; through day and often night. Their implements and machinery look rudimentary and unsafe. When looked at through a telephoto lens, one can see them work with a playful sense of concentration, with their lean, young, but able bodies. These are the real bodies of workers, much romanticised in political and art history. The scale of a young male body in a dense urban landscape makes for an intriguing conversation with the exalted body of the labourer or peasant, as represented in most cultures.

The video consists of observational material, looking at these young workers demolish and rebuild the city, at different times of day, across different seasons.

Karthik Dondeti

The Discomposition Machine

software code, 24 inch screen

2018

Ideas about development within the public realm are received by people through several sources that flow through informal and formal channels. These are recorded in the form of reportage, journals, public announcements, popular discussion and independent reflections over the internet. Such literature becomes the field for imagination of occupying the yet-consolidating urban landscape. Drawing on five such online archives indexing architecture and construction since the last national elections, this project invites users to build “news” through the discomposition of text. The code created by architect and coder Karthik Dondeti harnesses fragments of text from chosen sources turning news itself into a work of urban fiction. It is here that the project makes a political commentary on the narrative of developmental politics.

Nisha Nair-Gupta

Love Under Construction

artbook, digital print

4 × 6 inches

2018

‘Love Under Construction’ is a record of contemplations conceived in the longing for a companion and/in the city of Mumbai in its continual process of infrastructural transformation. Strung through metaphors of construction, and impressions of splashing concrete, city and life hallucinate and metamorphose into each other.

Poonam Jain

Looking forward : Looking backward

water color on paper

91 cm × 150 cm each (set of four)

2018

Poonam Jain’s immersive water colours attempt to inhabit the landscape of construction equipment, scaffolds, large scale moulds, machines and frames within which the phenomenological experience of the city is suspended for the everyday passerby. The everyday act of looking forward and backward gets reconfigured when parcels of areas that we access regularly are cordoned off, diverted, blocked, rerouted. Tiny doorways within huge forms hint at the new passages created within the crevices and gaps of construction infrastructure, which also become temporary homes for migrant labour. Poonam’s drawings encapsulate the experience of entangled manoeuvrings of urban space in the prolonged state of being under construction.

Pratap Morey

A Tension - II

ink on Korean Hanji paper

79 cm × 143 cms

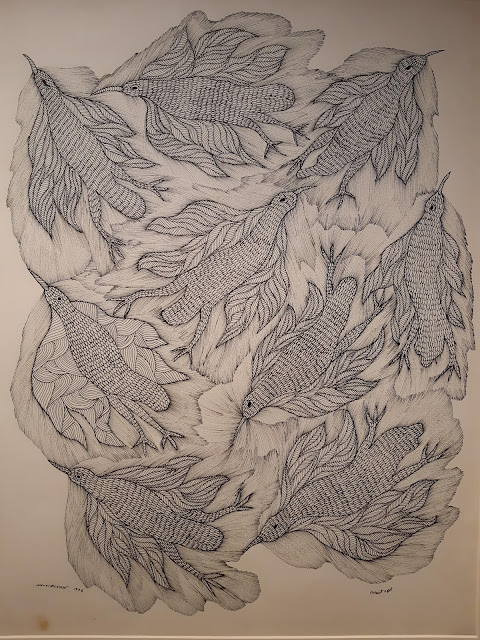

2017

Borrowed from the series ‘A tension”, Pratap Morey’s work presented here reflects critically upon the new infrastructures built for frictionless commute – namely the skywalks and the metros. Lifting up the people from the “messiness” of the ground, they often get too intimate to direct passers-by to peek into kitchens and bedrooms of those whose apartments are too close to these skywalks. Morey draws his artistic language from the superimposition of these infrastructures to highlight the fragmentation of the sky, the splitting geometry of cityscape, and the forever increasing tension between the old and the new.

Ritesh Uttamchandani

Afterlife

photographs on flex

10 × 10 feet, 10 × 3 feet

2018

Photojournalist Ritesh Uttamchandani notes: “As I move through the city of Mumbai, I am always looking for photographs - things with subtle humour, exploring not the beginning or the end, but the in-between. In the run up to the General Elections of 2014 and subsequent State elections after, I noticed a booming of political propaganda posters. In spite of various legislative actions banning these hoardings, politicians continue to use them in campaigns - directly or otherwise. Over time they have only gotten bigger and unpleasant.”

Afterlife is a photograph series that emerged from the ways people innovate these flex pieces into their everyday constructions. Upcycled by the city dwellers, they are used as covers for shops, sleeping mats, protection from rain or even temporary shelters. Of the several promises that politicians make over election campaigns - those including employment, pothole-free roads, healthcare, housing, etc.; these political flex-banners come to fulfil at least some, although quite amusingly, in their afterlife.

Shreyank Khemalapure

Waiting Bars

construction models

mild steel, galvanized wire mesh, borax, wood, fine aggregate

dimensions variable

2018

‘Waiting Bars’ is a building construction term, referring to the steel reinforcement bars left open ended in columns and beams to receive future additions. ‘Waiting Bars’ thus literally wait to take on more construction, or further life.

Typically, additional foundations and columns are left around the existing building (even after completion) such that a couple of floors can be added above, or rooms can be extended sideways. Such frames give a unique character to buildings in the city, that have extended arms and frames around them.

This work attempts to extract ideas of time and growth embedded within construction processes and is derived from these incremental actions and their resultant architecture. The objects presented here are under construction as long as the bars are waiting.

Sunday, November 25, 2018

On Kitchens (India)

CONVERSATION 1

1. How have kitchens changed from the time of Independence to present times vis a vis - its, shape, size, lighting, how it is located within a house, attachments, equipment?

It is important to note the practice of cooking and its resultant spatial implications on the planning of the house, when studying the Indian condition. Historically, cooking spaces must have been a ground activity where much aspects of food: from preparation to eating would take place on the floor of the house. In India, floor allowed the kitchens to become more social, allowing women to get together easily towards preparation and sharing of work. Apartment living comes into our milieu by the early 1920s, when the kitchen gets formalised into a room within the house. Early modern kitchens (in India) already usurp the terrestrial kitchen to a raised platform, making the sitting women stand. They also transform the kitchen activity into a sort of "assembly-line" : cutting-cooking-washing! The linear platforms bring in a new idea of organization and sanitation but at the same time complicate the hierarchical relationships of gender, caste, class w.r.t. the ideas of sacred and profane.

Several older apartment plans will show more than one door to the house - one for the toilet cleaners, one for the maid and the last for the owner. Thus kitchens would have their own service doors to keep the maids or cleaners (who belonged to a lower class) separate. Modernity thus got assimilated with deep contradictions.

For a long time, cylinder was the key object of the kitchen, around which storage spaces were planned. Steel utensil organizers can still be seen in some households. Refrigerators and ovens changed the planning of the kitchen significantly - and made the presence of electrical points within the space essential. The geography of the kitchen changed after the introduction of the piped gas, and the rapid take over of the modular furnitures. In recent times, one sees the shrinking size of the kitchens in the planning of apartments. The kitchen is seen as a mere functional space where social interactions within the house do not take place. Hence, their space is released into the other areas of the house. Dining - which once was a table, has now become a "Space" within the house. One often sees the dining notches carved out in living rooms in present-day apartments very evidently.

2. When did the change start from broad, expansive kitchens to smaller versions - both in India and abroad, what influenced this change?

Several socio-economic dynamics have also affected the way in which kitchens are imagined. Seen as an activity that does not contribute to the capitalistic process directly, household cooking (and therefore the kitchen) is often undervalued space, reduced to a storehouse. Such a move has serious implications that need to be studied. Moreover, one needs to understand how it gets gendered and further, what socio-cultural rubrics it operates within different castes and classes across different regions within India.

3. How popular are open kitchens in present times? What is the reason for the popularity and when did this change start taking place?

Open kitchens allow to merge smaller spaces into a large one, and help releasing space. In patriarchal setups however, where households operate on strict rules for women, kitchens are still not opened out to the public parts of the house (like the living room). The open kitchen perhaps became a way to symbolically claim values of modern living and lifestyle. Although having an open kitchen would necessitate its organized look at feel, forcing attention towards hygiene and cleanliness.

4. Do you think that traditional modes of cooking and equipment are now in danger of disappearing forever with the change in the size of kitchens? is it good or not desirable?

Is there a monolithic traditional mode of cooking? I am wondering what values are you trying to invoke in the traditional? Instead of the fear of disappearing, we must looking at the process of cultural transformation of the kitchen and its resultant effect on the human body. Improved amenities within the kitchens have certainly brought more dignity to the person who operated the kitchen - in our case, primarily the woman. If modern amenities are able to release time for women to participate or engage equally in activities that she could not pursue before, then such transition is welcome. If we are able to ascertain what values of the tradition and traditional equipment do we wish to retain, we may be able to bring it to our modern lives and amenities. However, traditional modes of cooking and equipment may also be deeply feudal and gendered and for once, we must consider the virtue of their disappearance too!

5. The concept of mess kitchens or work areas to supplement the kitchen space seems to be in vogue now, can you tell us a little about this?

Such spaces can only work within extremely communal societies. With strict ideas of the sacred and profane within the different classes and castes, food is a complicated affair in Indian social space. Community kitchens have been experimented in many places, but most operate within a single caste-group (you can think of the langars in Gurudwaras). I do not know about the "mess kitchens" that you point out.

CONVERSATION 2

Hi Anuj,

A quick clarification - I am not really sure what you mean by this:

The linear platforms bring in a new idea of organization and sanitation but at the same time complicate the hierarchical relationships of gender, caste, class w.r.t. the ideas of sacred and profane.Please can you let me know what you mean by this?

Thanks

Dear Fehmida,

In older traditions, the processes of cutting, cleaning and cooking were often dispersed into different locations of the house. The house itself wasn't a BHK type (apartment type). These locations indexed certain hierarchical relationships that structured the overall process of consumption. With the introduction of the modern kitchen, all these different activities are streamlined into one room, more specifically onto a single platform counter. Interior designers and space planning manuals will tell you how these need to be organized for efficient functioning of the kitchen in modern homes. Thus, we see these kitchen counters with a space for preparation, cooking and washing (in that order) provided in a line - almost like an assembly line fashion. Such planning of the kitchen is generalized within newly built apartments to which, residents have to stick to (despite their alternative cooking practices). Those who can afford, alter their kitchens in order to continue older customs. However, within the standardized geography of modern homes (BHK type), these changes do not really offer much scope, and the most optimum solution is to stick to the linear platform.

The linear platform forces, to be sure, the people involved in cooking to be on the same counter. Given the deeply culturally coded gender roles in our heteronormative society, the kitchen can be seen as an instrument of divide or unision - for in the progressive, liberal families, the man and woman will be able to work together, however, in more conservative and traditional families, the kitchen will remain the domain of the woman, pushing the man out. This is my theoretical speculation.

Secondly, a lot of households still follow ideas of 'jhootha' or 'aitha' - which indicates that any thing eaten or partly eaten (even tasted / anything touched to the mouth, or touched with an impure hand) should not be mixed with the fresh stock - including vessels that contain them. The water pot is sacred, for it is worshiped and changed every year on an auspicious day. The used dishes and plates should be kept away as a matter of hygiene. The platform with the embedded sink does two things here: 1. It mixes up these "used/dirty" utensils with the fresh ones. The sink is also the place from where you draw water to clean things - thus the place of cleansing is also the place that accommodate the unclean. 2. The maids (who are often seen as a lower class, may also belong to lower class) now come on the same platform for cleaning the vessels. Traditionally, the place of cleaning would be outside or away from the cooking space.

Again, these are my theoretical speculations.

I hope you now understand my point on the complication of hierarchical relationships of gender, caste and/or class. One can present many case studies to bring out different shades of how modern apartment kitchens negotiate or work out these differences.

Let me know if this helps.

Best.

Anuj.

Saturday, November 17, 2018

Misreading

Sunday, November 11, 2018

On Architectural Writing // interview by Shriti Das

The country has eminent architecture schools and equally prestigious media institutes. But did the two ever meet, formally? Not really. Architectural writing is not only gaining momentum in the media and architectural fraternity but is also an important tool that communicates design to architects, other professionals, enthusiasts and the masses. CQ speaks to Anuj Daga, an architect/writer, and Sharmila Chakravorty, a media professional, who write on art, architecture, design and allied disciplines about the many questions and misconceptions that riddle architectural writing.

If we can agree that all built spaces tell stories, then writing perhaps might be the most direct and effective way of narrating them. To write about design is to release a range of invisible nuances that an object may not lend you easily. The writer allows users to read new forms in which the work might be appreciated across history and geography, and thus makes the act of design democratic and universal.

2. How is design writing different from journalistic or story writing?

It’s not. Design writing can take different forms including journalistic or a novella. In most successful instances, it will bring critical attention to human acts and the manner in which they shape their ideas into material.

3. How did your design education help in this field?

Design education lent me a range of tools through which one may begin to articulate aesthetic experience. It opens up to a range of methods and parameters to appreciate things around us. Of course, these keep on changing and evolving with time. For example, ‘proportion’ and ‘scale’ were important parameters of assessing architecture that were introduced through design education. Today these parameters may seem archaic given that we experience much of space through media and the virtual. This example also illustrates how architectural and design history maps the shaping of our choices today and are deeply embedded in certain cultural and technological conditions of time itself.

4. How do you perceive a building critically and analyse it?

A sensitive observer necessarily has a deep sense of “self”, which is shaped through the cultural and social factors around himself / herself. Noted French literary figure Geroges Bataille once said that “Architecture is the expression of the very being of societies, just as human physiognomy is the expression of the being of individuals.” Simply understood, he meant to suggest that just like physical features of human beings may tell about their character and behavior, buildings express the aspirations and intentions of a society. The parallel between body and the building is compelling, and often, the process of perceiving a building is to understand one’s own experience within it with sensitivity and awareness.

5. How do you write about a building that doesn’t appeal to you or incline with your personal design belief?

More often than not, an unappealing project is an opportunity to expand my own limits of aesthetic experience. Often when I encounter an art object which I do not relate to, I have to inform myself about the cultural context it comes from. While the research helps in opening up new dimensions of seeing, it is also a reminder about one’s own cultural positioning, and the compulsive need to broaden it. Besides, design beliefs, like our very identities are malleable and transform themselves with time and experience.

6. It is believed that practicing design has more “scope” than writing about design – in terms of career, money, stability. In your experience, how true is that?

It is high time that we discard prejudiced cultural baggage we carry from a certain pre-liberal India and acknowledge contemporary architecture’s expanded field where the figure of the master architect continues to get blurred by a range of allied design practitioners who equally partake in shaping the final experience of any object or space. Besides, in the wake of increasing media and internet consciousness, conventional practices are realizing the value of archiving and communication. Given this change and there is more scope for design writing now, than ever. To the least, one can say that conventional building practice runs the same risks as design writers. Good projects will seek good writers. However, in order to bring value, design thinking, and writing has to take centre stage in education process.

7. What would your advice be to someone starting out in design writing?

Much of our design institutes (in India) are not equipped in introducing students to design theory. It is important that those interested in writing have a theoretical and analytical bent, so as to clearly present arguments about experience of an object/space rather than descriptive reviews that are often evident in their visual documentation. Focused reading and writing helps sharpening one’s own voice and way of looking. With ample written / visual content and free courses available on the internet by renowned universities, one must look forward to introduce themselves and expand their existing ways of thinking.

Thursday, November 01, 2018

Life Notes

Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk, teacher, and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh