I first visited CEPT in 2003, in my first year of architecture school - when I had instantly fallen in love with the place. The rustic brick, the silent courts, the student life encrusted in its space - all made it almost spiritual. I have regularly visited the campus since, and seen it changing until today. Somewhere during 2010, the large classrooms once cubicled and personalized by 40 students, bathing in natural light and air had been partitioned into to air conditioned rooms. It was no longer the peaceful campus of Ahmedabad I had visited. Neither did it remain the mythical ideal institution - a building of architecture that espoused the very ethos that it imparted within its students. The new arrangement seemed impersonal and logistical.

The taking over of CEPT by the new director Bimal Patel has kept the overall intellectual and physical development of the campus in high controversy. With an increase in the demand for post graduate education in India, the need for more space and facility, the buildings on the CEPT campus have rapidly expanded. The plots on the fuzzy edge of the school, have all been given up to different architects to create new buildings for the growing needs of the institution. Over the last few years, the likes of Rahul Mehrotra, Gurdev Singh and recently Christopher Benninger - all noted architecture practices in India, have been appointed to design new buildings on the CEPT campus - all which have been received with measured reluctance. The campus design has been held in reverence of the architecture school building's humble sections by Pritzker Laureate Doshi with its soft flowing volumes into the adjacent natural settings. For some reason, we all always assumed that the wilderness of the campus shall be eternal, that it will always allow adaptive use through its informality.

Ahmedabad is often spoken of as a 'Mecca' for Architecture in India. It's a city where ambitions of nationalism, modernism and regionalism converge. To say the least, it's a land where the modern European masters built some of the most significant buildings of their career. Ahmedabad is one of the few cities which boasts five buildings by Le Corbusier, and a large campus by Louis I Kahn. Ofcourse, it has remained Doshi's backyard for architectural experimentation and remembered for one of Charles Correa's first and most revered project - the Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya. Subsequently, architects have visited the place for the intellectual apparatus it lent for the discourse on modern architecture in India - producing a range of practitioners carrying forward the legacies of the above modernist 'masters'. The reverence and emotion for purity of the built object in Ahmedabad is thus, understandable. Every new project that comes within the radius of these masters is aggressively debated, critiqued and discussed. The buildings of Mehrotra on CEPT campus has been one of the victims of such evaluation.

This time however, when I visited CEPT, things seemed okay. Perhaps I was prepared to take in change, perhaps the new buildings were now inhabited and functional, or perhaps because it was just nice weather... As a non-emotional alien to the campus, I was keen to understand what these new projects do to the campus. Mehrotra's library became infamous over its exposure to first rain which brought in a waterfall through its reverse plinth slopes. The matter was corrected, and now, you enter the library through an exhibition-pavilion which is frequently used by the students across campus as a shortcut (in whatever way). The ground floor of this building is thus open, and public in nature, and establishes an axis with the architecture school. Its plinth separates the building too harshly from the remaining campus, and is too barren as compared to Doshi's treatment of the architecture school underbelly.

The stacks however, are staggered interestingly, for they split levels to suffuse within them reading spaces. A study of the section reveals different degrees of enclosures that they create for various kinds of reading experiences. Thus, browsing and reading are no longer separated, rather they assume a book-shop like character where visitors are able to stay within the book walls while reading. The furniture is cleverly orchestrated to perform as parapets, ledges or racks at the same time. The stacks take up the central volume, much like the Bienecke library at the Yale University, although humanized in scale, and improvised on its skin detail. The peripheral volume accommodates smaller carousels and desks for quiet readings and are said to be always occupied. While one would think that the sunken space is hermitically disconnected from its immediate surrounding to read, Enakshee, a graduate student at CEPT, who took me around explained that many prefer the quiet detachment. She said that the library is always full, and it's difficult to find space to work here. Whether the increased use of the library is a function of new design or a signifier of lack of space is something that needs statistical analysis, but was an encouraging marker.

The upper floors are reserved for reading journals and periodicals along with e-work stations. Some people may find the space too lifeless, for the connection to the environment is lost further; whereas for a reading zone, it's inertness may virtuous. The entire library is now a closed box which two tall bands of adjustable vertical louvres on its facade through which one may control the light entering the volume. One may appreciate for its simple inventiveness and the possibility it lends through intermediate catwalks to clean the glass panes. All in all, I was pleasantly elated about the updatedness of the library facility at CEPT. Two remarks probably summed it over my conversation back in Mumbai. Rupali summarized that the CEPT library is an example of a good American building on its campus - a neat contemporary design that fits well within the geopolitical aesthetics of architecture today. Prasad quipped on my remark over its updatedness: they reached here at the fag end, when the Universities over the world are ready to shun physical libraries altogether.

The other edge firmed up by Mehrotra was the canteen corner which once used to be a series of charming stray ledges scattered over an undulating set of mounds under the campus trees. The area now boasts a hard plinth with ramps to make the place accessible. Above the canteen is a large review facility with large halls and a wide corridor that is allegedly proposed to be connected to the new building under construction, designed by Christopher Benninger. Meanwhile, the canteen building trails in the other direction through an almost monumental dogleg ramp, solidified on its underside. The midlanding of the ramp dissolves into a mini amphitheatre, which to me, saved the edge from becoming too sharp, and opening up a yet another performative corner.

What appears to be a large construction site right now across the upper floor corridor-balcony of canteen today is an apprehension filled project by Christopher Benninger. The building is supposed to host a large auditorium, spaces for staff, and the architecture department. This would mean Doshi's design to be released as free space that may be appropriated for activities we don't know yet. All this sounds rumour, but Ahmedabad is a place where architectural rumours often turn into reality! But someone who is really interested further must read the passionate letters

here and

here and

here towards revising the proposed design that harks a deeper vision, empathetic engagement and conceptual clarity to the block that is rising up.

On the other end of the campus is a centralized fabrication lab facility for CEPT which has been designed by Gurudev Singh. The building works through a simple functional design of a shed, and extremely well detailed - simple and clean. The voluminous spaces bathe in sagacious light. To some extent, the design sectionally draws from Corbusier's Chandigarh College of Architecture, but removes all heaviness of concrete and replaces it with sleek open web steel beams that seem to have been imported from Sweden (?). The design is a no-nonsense response that serves really well to students in bringing technology and craft together. It is one of the few workshops in India which boasts a space for lithography, while trying to get closer to more recent technological tools.

Overall, the campus is now a checkered grid of built and unbuilt pockets: precisely like a chess board. You move from one courtyard to another passing through three storey masses. Certainly, it began to feel like a western university campus, losing its revered ambiguity and wanderings. While the new buildings seem too bookish, the critiques too seem to come straight out of the text book. After reading the letters linked above, I began to wonder if these conversations became too didactic? The deification of the campus is phenomenal, to the extent that it assumes the status of modern heritage (which it may rightfully be, especially after Doshi's Prtizker).

It's not as if responses to heritage need to be docile and as human. For example, in the MIT campus in Boston, Charles Correa's Brain and Cognitive Science building does stand quietly as a background to Gehry's Stata centre, or Tschumi does provoke a new phenomenological reading when he inserts his follies into the Park de La Villete. The manner of critique could have demanded an innovative conceptual exercise that would suited the spirit of the contemporary instead of extending a nostalgic romantic past. There are often deeper conceptual critiques that theorists and academics bring to reject the new buildings on the CEPT campus. I think it is a worthwhile exercise. I feel that's why we have Ahmedabad and the legacy of Architecture with a captial A.

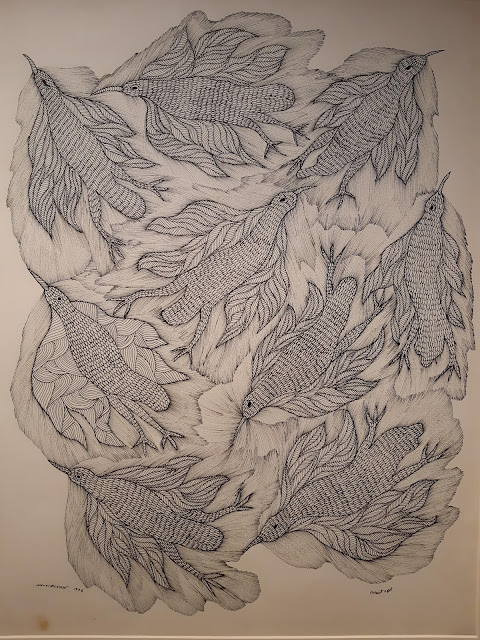

(the images below are not in order, but should serve as a provisional index to the above piece)