"Electricity is my material," said Ashok Sukumaran recalling what he told Geeta Kapur long time back. With some courage and eagerness, Ashok seemed to have asked the prominent art critic if she would contribute a text for an exhibition. Geeta, an established art historian having documented the arc of Indian art in the traditional modes of production, felt that she did not exactly understand the medium Ashok was working in. She therefore decided to excuse herself of writing for it. Ashok, a then-emerging new media artist having finished his MFA studies from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), USA, continued his experiments and works with his novel "material". Ashok's exclamation and the response by the art critic articulated the 'new' in the new media for me. It resolved, right in the initial days of my work with CAMP, a host of questions that I was carrying for a long time regarding the underpinnings of 'new media'.

What would it mean for an artist's material (medium) to be electricity? How does electricity - something that one cannot see or handle, something that is always escaping, dissipating and fugitive in nature & form, become material? What kind of art does it shape into? What does it mean to use electricity artistically, and in what way can one craft electricity? As a studio assistant, I was excited to be able to witness how CAMP crafted electricity and its forms, and further to see how their works come together in their exhibitions across four galleries in the country - namely Kolkata, Delhi and Mumbai.

To be sure, this exhibition series was retrospective in nature, allowing CAMP to showcase much of its past works (experiments). CAMP decided to weave together different projects for each of the four exhibitions into sharp themes, held together by the idea 'As If'. The umbrella-call for 'As If' is intelligent and clever - it offers to claim a reality that has not yet taken place, but looks possible. It brings together metaphor and expectation, comfort and risk, challenge and play, creating excitement and soft fear. 'As If' creates new tendencies to look at the past as well as the future with these attributes. In fact, it resonates with the nature of the artists' primary medium (material) - electricity - that exists, but can not be seen or handled directly.

The first show of CAMP opened at the Experimenter Gallery in Kolkata, titled 'Rock, Paper, Scissors'. The works included in this exhibition aimed to challenge the tripartite equation between the 'author', 'medium' and the 'subject'. I took some time to understand this system and discussed one night with Ashok, when he explained this concern primarily seen in much of Shaina's work. To quickly summarize, when an artist works with a medium, he/she uses the medium to produce a certain experience for the viewer, in other words, a piece of work is often authored carefully by the creator to draw specific emotion off the viewer, or in other words, the subject. In such a situation, the subject, often unaware of the intent of the author gets further inscribed in the medium, becoming a passive consumer. This indicates the vulnerability of the subject to the author as well as the medium (for he/she may be unaware of the workings of both). He/she is essentially subject to a force that seems beyond reach. How can such hierarchy be challenged, or even broken?

In the game of '

Rock, Paper, Scissors', each individual is in control of his/her choice, having equal possibility to turn the game. Three works of CAMP were installed in this exhibition, pushing the question of

author,

medium and the

subject to the viewers. The first one was a film created out of a CCTV footage in Manchester City's Capital Circus. The second was a Windscreen - an animated sculptural screen made out of paper, straw and wires. The last project was called Khirkeeyaan, where a combination of CCTV technology and TV screens (a preliminary skype technology) enabled people within a neighbourhood to communicate to each other at their will. While I primarily worked on the Windscreen, the experience of which I shall be able to share in more detail, I will try to touch upon the other two briefly.

Originally executed as a part of a video class during his masters, the Windscreen was "a joke on video", said Ashok. The installation consists of carefully cut rectangular paper pixels strung on to metal wires by means of an attached straw. These pixels, when subject to air pressure (created by a fan) would be flung off straight onto creating an opaque screen. Any person passing between the wind and the screen would block the air, creating his/her own "shadow" through the fallen pixels.

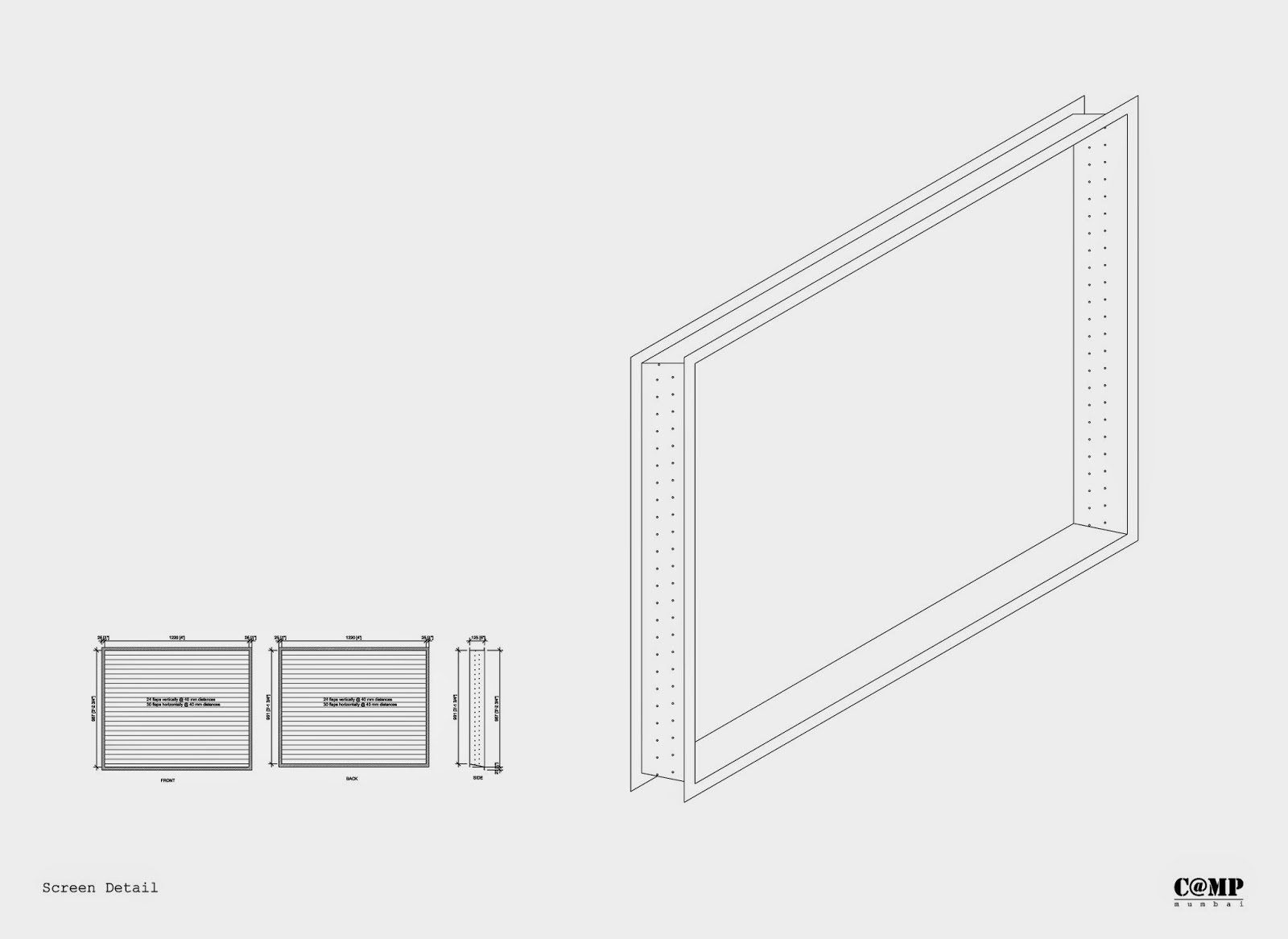

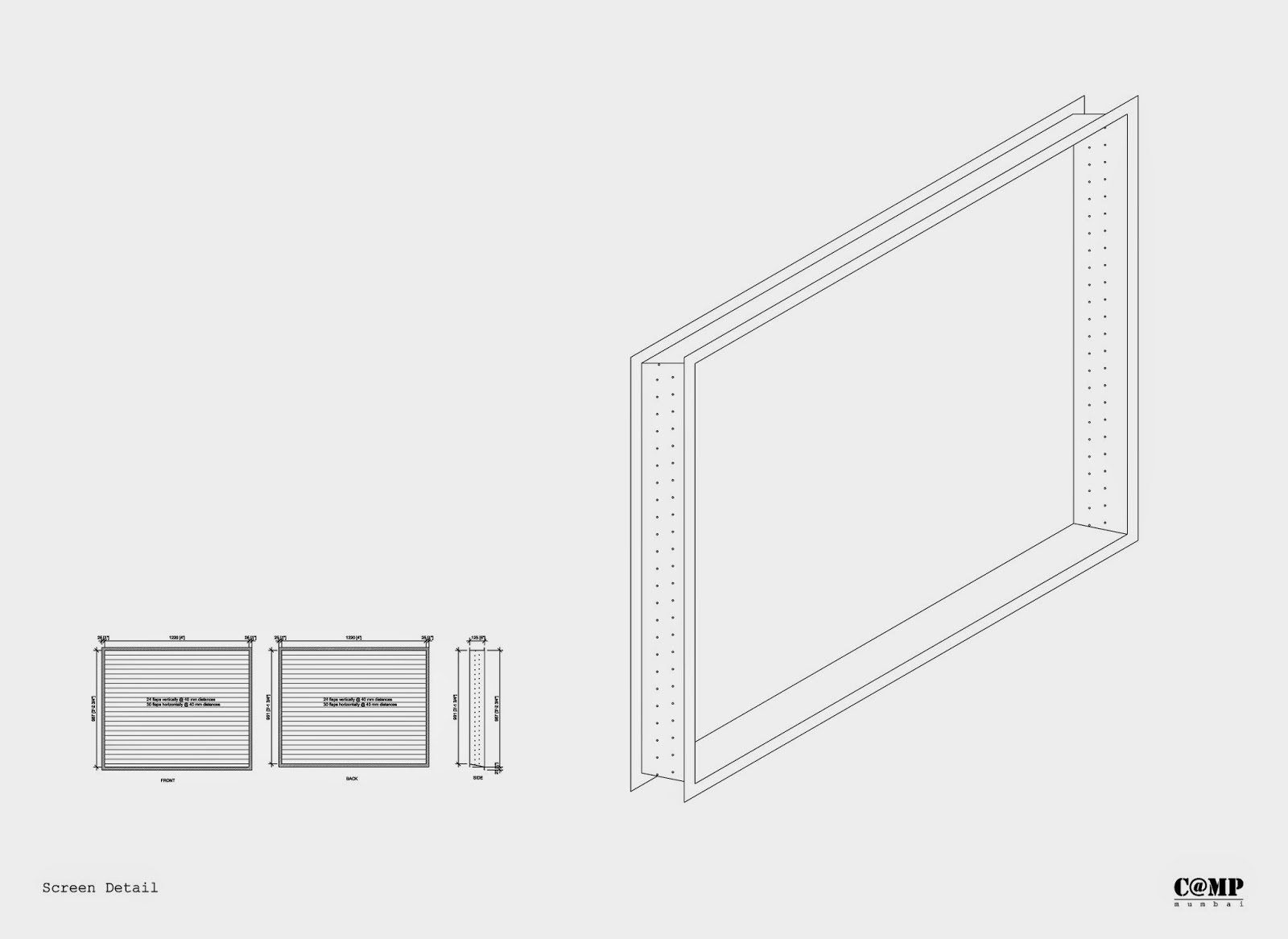

For me, the beauty of the screen lay in its extremely simple and frugal construction. First, the frame was fabricated in steel through a local guy who makes metal furniture. To be sure, the proportions of this screen (and all subsequent ones) followed the pixel ratio (4:3). In order to string the pixels, holes for wires were made at precise positions to hold these when at rest, and when flung. The wires were arranged at a careful angle just enough to air lift the paper pixels. The pixels were cut out of translucent parchment paper. The next step was to stick to them a piece of straw so that they could be strung on to the wire on the frame. For his first project, Ashok had sneaked a considerable amount of straws from the Coffee Shop. These straws had three holes, and were brown in colour. If stuck on the paper directly, their dark colour would be too much of a visual disturbance. Thus, they were stuck using a double sided tape onto the paper pieces - about 840 of them!

My first task was to labour this process, which I thoroughly enjoyed. Cutting the paper, and then the straws in anticipation of making a kinetic sculpture kept me going. It took me three half-day sessions to cut paper for the first windscreen. Then I got on to slicing the coffee straws. Ashok cut the double sided tape. We had to slice the width of each piece into 4 thin pieces - a job quite tricky due to the sticky nature of the double sided tape. The entire process was extremely architectural, for we were literally cutting paper and plastic to construct modules for an assembly that would eventually move to air. I can go on and on sharing my learning from this week-long exercise: it made me quiet, focused and productive.

In the process we would occasionally pause to rethink our methods of being more efficient. Ashok would try to remember how he produced the raw material for the first time, while I shared my own experiences of actually doing the job. One of the prime concerns was to tackle the moisture that would affect the paper, causing it to warp, reducing its effective dimension and causing it to slip through the wire framework. Another "bug", as Ashok would say (borrowing from electronic field), was the two adjacent pixels sticking to each other when strung along. This was due to the double sided tape thickness touching the other. This was a serious problem considering that the fan air pressure was maintained just that it would lift the weight of one pixel (read paper - now a physical pixel). We had to make sure that no two pixels stuck together, for it would increase the weight of the pixel. The three holes of the straw also played a role - we had to be sure to string the pixels through the topmost hole. The pixel would fall back to its position only if it had just enough counter weight. Thinking of all such parameters was sensitizing.

We tried to avoid the moisture by keeping pixels in the interior, given that CAMP studio is right across the Carter Road. In order to avoid sticking of two adjacent pixels, I suggested to sprinkle talcum powder on the sides of these tapes. We learnt about each material much closely. Weaving the wire through the frame was also quite a process, for we couldn't allow it to be loose, and neither could we pull it too hard, when it would give away. The wire kept losing its elasticity constantly - when we also happened to discuss Young's modulus! For the first screen, we had to replace some that snapped. Further, as we were serially pulling wires one by one through the steel frame to fix them tight, we realized that the frame was being pulled inwards, making the previously tied wires sag. Improvising our techniques thus, we began to become more careful on how to go about beginning and completing the project.

The project finished on time. And the pleasure of testing it for the first time was unimaginable. We took a wall mounted fan (of a particular size and power) and rested it upside down on a chair, placing a pillow underneath setting up an angle. When switched on, one by one the flaps fluttered. They created a soft sound as they flung and fell on the metal wire. The gliding was slow enough to see the pixels rise and fall. At a moment, it felt like the peacock's feathers, and at another, it reminded of the flutter of a bird. But more importantly it revealed to me the working of a video - the way in which the blowing wind activated the pixels created an opaque screen. When a person would pass through this, the profile of the body blocking the wind would make the corresponding pixels fall, creating a shadow. This phenomenon is much like the camera capturing an static or moving image. The windscreen had made many unseen things physical - in translating the photo rays as wind and the electronic pixels as paper pieces. It had translated the working of photography or video as if the medium was physically available to be crafted. It took me into the history of the evolution of photography (a subject that I had recently studied in depth), but at the same time heuristically made it possible to extrapolate and craft it for the future.

Beyond its own making, the windscreen creates a distinct reading closer to the theme of the show - the way in which the subject and object create a complete system. The user (subject) almost is in control of his or her image on the screen when passing through this system.

'Capital Circus' was a film made using CCTV footage collected from a large mall in Manchester City, Europe. A lot of work went into the sound editing of this video. Instead of being subject to the gaze of CCTVs the project gets inside the room where these footages are monitored and recorded. Further, people being filmed are made aware of the fact and asked for their permission for the footage to be used for this film project. The film raised questions on who can be filmed, when, and larger issues like surveillance and its politics.

Khirkeeyaan was a project in which new connections were made outside of the Cable TV system within a neighbourhood in Delhi through which people could see as well as talk to each other using their own TV sets and speaker system. I do not have any specific comments on the project, as it seemed a bit voyeuristic and too cumbersome an exercise in an age of the internet. Yet, such network would perhaps be more meaningful for areas with internet censorship, strong state control over communication and similar such restrictions. It might be interesting to consider using the freedom of this system from being tracked by any other. It creates its independent network, completely non-institutional. In this way, yet again, the users are empowered to harness the system for their own purposes. They only need to take over the infrastructure of media, infrastructure of communication.

It is inherently difficult to display media art because so much of it is virtual, and a gallery space often craves for a formal intervention. Even if paintings are static, they demand movement, which help navigate the gallery space in new ways. How does video and audio perform this task? The objects of display then, are environments created by such media constructed in video and sound. These are not physical, merely simulated. Structuring simulations of different geographies is a difficult affair within the contiguous space of a gallery. They tend to create an alternative experience, a reality different from those we actually see on screens. Media art always struggles to remain itself thus.

I am not much of a media artist and my understanding of these works is perhaps very limited. The above account has been purely descriptive - that's all that is left with me! Rather, that is what I took from it? I am also distanced from the concerns of media until it directly affects me. I can relate to these concerns but can not be instrumental enough to take action on this aspect. Beyond academic view, it is hard for me to politicize them. In my broad view, we live in a society where letting out personal information has not yet become a matter of concern. It is something that perhaps yet belongs to the developed societies. To that, we have not even interconnected our entire society. Yet, CAMP's works suggest a solution to the assumed warnings as the state makes way for smart cities and smart nation. It offers a pre-solution to issues that shall come to describe the crisis of the future.

(further reviews of CAMP exhibitions in subsequent posts)