Published in Art India, September 2016

Beyond Bricks, Mortar and Concrete

Anuj Daga dwells critically on a show that tries to map the state of the built environment in India.

“What do we exactly exhibit when we exhibit architecture: should we be satisfied to exhibit photographs of buildings and sites, or should we aim to put whole buildings or, if that is not possible, fragments and models of them on display?” These preliminary questions from the symposium ‘Exhibiting Architecture: A Paradox’

[i] can appropriately initiate a discussion into the curation, agency and politics of

The State of Architecture (SOA) exhibition at the NGMA, Mumbai. Organized along with talks, allied exhibitions and art events spread over three months, SOA attempted to draw the attention of the public to ‘practices and processes of architecture’ in India. To elaborate upon the initial inquiry for SOA, one may pose further, what is the experience of time characterized by technology, media and global flows? How does it touch ground and manifest as architecture in a country as diverse as India? How must it be artistically displayed for a critical review within the space of a gallery through the medium of an exhibition?

The State of Architecture, an Urban Design Research Institute project, curated by Rahul Mehrotra, Ranjit Hoskote and Kaiwan Mehta, from the 6th of January to the 20th of March, is notably the largest exhibition on architecture in India after Vistara that was curated by Charles Correa in 1986. While Vistara attempted to frame a pan-Indian identity unearthing the ancient mandala diagrams and traditional building methods over centuries, SOA establishes its orientation in the modern architectural profession which began as a colonial enterprise. It serves as a resourceful guide for young architecture students and aspirants – a convenient pedagogical tool to expose the lay audience to significant architectural development and production in the country over the last 65 years. Marking Independence, the Emergency of 1975 and the economic Liberalization of 1991 as the key moments in the history of India, the curators lay out the entire exhibition as a timeline of architectural and political events within the country.

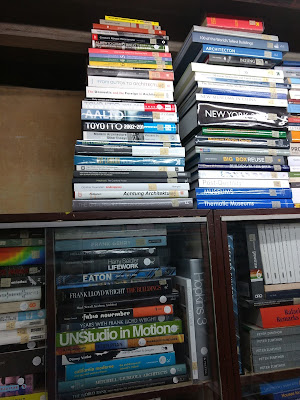

One is introduced to the current state of affairs in architecture at the entrance level. A large infographic translates data collected from the Council of Architecture records and other surveys to cull out seemingly urgent questions thrown all over the exhibition space: Why is there a low architect-public ratio? Why are few women architects practising? Why have architects become life-style designers? Does architecture matter? Do you need a degree to be an architect? Does capital dictate design? A selection of popular and frequently referred books are laid out on a long table that include monographs, surveys, reflections and memoirs, particularly on architecture in India. The number of books in this collection alarms us – there is an urgent need for a deeper discourse on architecture in India. Alongside is a wallpaper of architectural magazine issue covers. A comment on the quality of architectural journalism or reportage in India would help the thinking community take directed action.

The bulk of the exhibition, as we encounter in the split levels of the NGMA, is framed through canonized images pulled out of a handful of monographs of Indian master architects leaving behind the geo-political aspects of their work. This section talks about Nation-building Experiments, presenting a panorama of new cities, institutions and housing projects that were built under state patronage over the 30 years after independence. Most of these projects, as we may infer from the exhibition, were executed by a handful of architects – Charles Correa, B. V. Doshi, Achyut Kanvinde, Raj Rewal, I. M. Kadri, Habib Rahman and a few others. One wonders how the vast architectural landscape of India become available to a select set of architects. How did they gain credibility? Further, how did these architects interact with political power in deploying their works in different geographies? The curators state that the project of national identity was “renounced” by architects over the late 1970s loosening their modernist ideals to accommodate regional identities within their works. Whether such a move was a result of the shift in the state’s political ideology, or the architects’ struggle to address issues closer to diverse conditions, or a conscious attempt to align with the (popular) ideology of critical regionalism that emerged internationally as a resistance to the banal post-modern style, are questions not directly addressed, but bring out the relationship between how built form is intertwined within a large set of political forces.

Attention given to architects like Charles Correa, B. V. Doshi, Raj Rewal, among others, is indeed noteworthy. However, to be sure, these architects do not adequately frame the picture of the contemporary state of architecture in the country. Overshadowed by the above, a whole wave of architects mediating India’s transition into the corporate landscape have found no adequate space for discussion within the curators’ schema. For example, architect Hafeez Contractor, the most recent Padma Bhushan awardee, whose commercial architectural practice typifies much of the architectural production in the country hasn’t been a part of any serious discussion. Contractor’s practice is one of the first to crudely synthesize the inundation of global capital, imagery and ideas within our built environment over and after the period of liberalization, giving architecture a bold consumerist dimension. Many younger practitioners, those ideologically lost somewhere between Correa and Contractor, weren’t a part of any panel discussion.

The rotunda wall at the uppermost level was playfully animated – swelling and shrinking to reveal and hide projects essentially executed after economic liberalization in its folding skin. These are projects that disregard, rather, challenge our notions of indigenous architectural aesthetics. The contemporary projects displayed right under the dome of the NGMA begged for a sharper curatorial intervention – spatially as well as organizationally. In laying out panels orthogonally in four quadrants of the circular floor under the hemisphere, the exhibition missed the opportunity of harnessing the volumetric geography of the rotunda to spatially evoke the experience of architecture as a global product. On the other hand, it was perplexing to see a café besides a capitol, a school besides a factory, a hospital besides a house – losing the viewer in projects with disparate descriptions, situated in diverse geographies. The selection of projects clearly suggests an imbalance, only representing a handful of cities that have been frequently discussed over publishing platforms in recent times. It is here that the exhibition could have offered new conceptual categories to read and analyze emerging hybrid architecture that is otherwise lumped as ‘plural’. Lacking actual fieldwork, SOA hardly offered insights into aspects like the diversification of the profession, the remoulding of the architect’s identity or even the reconstitution of architectural practice in a globalized environment. A longer, sustained investigation would have revealed the specificities of reception of global currents by often under-represented states of the central, north-eastern and eastern belts of India.

The State of Architecture exhibition did not sufficiently engage with the questions I raised at the beginning of the review. It is unfortunate that the curators could not bring in even a single architectural model to the gallery. Rather, the only object that the gallery boasted was a copy of the life-size Manusha icon – that which the viewer was greeted with in the 1986 Vistara exhibition. Its inclusion in the present exhibition was merely fed by nostalgia. The conventional display of images within one of the most spatially exciting galleries of Mumbai seemed undemonstrative. To be sure, the only moving images (in the age of digital media that we live in) were a couple of films of/by Charles Correa, nothing which explored the (contemporary) state of architecture in India. With such a limited collection, its non-polemical presentation and frail engagement with multimedia or multidisciplinary inquiries, should one be satisfied by the overall experience of the exhibition?

It is indeed difficult to map the state of the contemporary built environment for a country as diverse as India with each state having its own political tectonics. However, can the questions asked for the built environment produced by a country of 1.2 billion be as homogenous? A more culturally relevant question to ask would be similar to that which is often posed in the rejection of the use of the term ‘Bollywood’ by many Hindi film actors and scholars. Brushing aside the downgraded labelling of ‘Bollywood’ as a portmanteau of ‘Bombay’ and ‘Hollywood’, they maintain that while the tools for producing films were received by India from the West, the Hindi film industry developed its own unique method of musical-narrative sequences in their story-telling. In this vein, it would be worthwhile to initiate an enquiry into the sense we have made of ‘architecture’, over the years post-Independence. How, and to what extent, have we come to redefine our values, and whether or not we are able to express them successfully within our built environments? This would give an opportunity for the object of architecture to become self-critical, contemplative and meaningful.

Much of the discussions in all fields, including architecture, are becoming highly technocratic, foreclosing any give-and-take about issues of culture and philosophy, thinking and making, living and the self. If understood as an act of creative production, this exhibition falls short in bringing forth any discussion on the politics of design in the execution of its material. Architects’ materials today have reduced to brick, mortar and concrete – no longer does poetry, literature, music or philosophy come to shape the built environment. Likewise, drowned in mere visuals, SOA fails to provoke the viewer into thinking deeply about the meaning of her surroundings. The incapacity of many architects to absorb, interpret, critically reflect and translate the cultural zeitgeist of the country in their works characterizes both – the state of architecture in India as well as the exhibition of the state of architecture in India.

End-Note

[i] “Exhibiting Architecture: A

Paradox”, Concept note from the symposium held at Yale School of Architecture,

2013.