Thursday, May 17, 2018

Tuesday, May 08, 2018

To believe in oneself

"Persist and verify…The power that we abdicate to others out of our insecurity — to others who insult us with their faux-intuition or their authoritarian smugness — that comes back to hurt us so deeply… But the power we wrest from our own certitude — that saves us."

Rosanne Cash / excerpted from Brainpickings

Rosanne Cash / excerpted from Brainpickings

Saturday, May 05, 2018

Orientation

The concept of "orientation" allows us then to rethink the phenomenality of space-that is, how space is dependent on bodily inhabitance. And yet, for me, learning left from right, east from west, and forward from back does not necessarily mean I know where I am going. I can be lost even when I know how to turn, this way or that way. Kant describes the conditions of possibility for orientation, rather than how we become orientated in given situations. In Being and Time, Martin Heidegger takes up Kant's example of walking blindfolded into a dark room. For Heidegger, orientation is not about differentiating between the sides of the body, which allow us to know which way to turn, but about the familiarity of the world: "I necessarily orient myself both in and from my being already alongside a world which is 'familiar'" (1973: 144). Familiarity is what is, as it were, given, and which in being given "gives" the body the capacity to be orientated in this way or in that. The question of orientation becomes, then, a question not only about how we "find our way" but how we come to "feel at home."

Ahmed Sara, in Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, Duke University Press, London. 2006. pg. 6-7

Wednesday, May 02, 2018

Monday, April 16, 2018

The Craft of Smell

In true sense, the work of art at the Sassoon Dock was the containment of people in an overbearing envrionment of smell. It is the smell that defines the dock - which kept intensifying and reducing as one moved across the different chambers opened up for art installations at Mumbai's historic dock. One notices the largeness of these left over spaces that have remained locked for a long time. Opening these to the public makes one appreciate the architecture of a dock.

The smell becomes a part of you in a while, after which you are reminded of it through different installations within the exhibition - the toilets, the sea, the perfume and so on. At the risk of becoming too obvious, the assertion of smell as an art form was refreshing. It takes one out of the sanitized environment of the white cubes and brings you to reconsider the city wherein you are constantly negotiating olfactory environments.

Typography and Graffiti was an important part of art, primarily because it was curated by ST+ART Mumbai. Different parts of the city were taken over by street artists from all over. The exhibition saw a new politics in art making. Most importantly, it opened up the docks, which, while leaving, are the strongest memory that remind you of the city as a key trading harbour. The jetty, the warehouse, the left over luggage and sea leave you in a wave of history that is so close, but yet seems so far. It was totally worth visiting the place taken over by art!

Sunday, April 15, 2018

Saturday, April 14, 2018

Gyan Panchal / Against the Threshold

Object Lessons

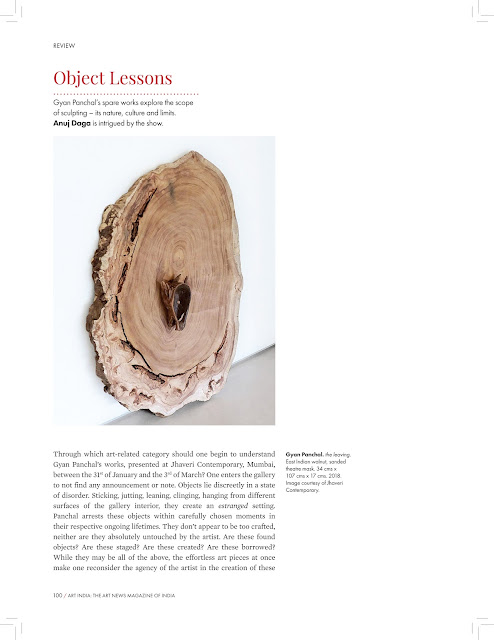

Gyan Panchal’s spare works explore the scope of sculpting – its nature, culture and limits. Anuj Daga is intrigued by the show.

Through which art-related category should one begin to understand Gyan Panchal’s works, presented at Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai, between the 31st of January and the 3rd of March? One enters the gallery to not find any announcement or note. Objects lie discreetly in a state of disorder. Sticking, jutting, leaning, clinging, hanging from different surfaces of the gallery interior, they create an estranged setting. Panchal arrests these objects within carefully chosen moments in their respective ongoing lifetimes. They don’t appear to be too crafted, neither are they absolutely untouched by the artist. Are these found objects? Are these staged? Are these created? Are these borrowed? While they may be all of the above, the effortless art pieces at once make one reconsider the agency of the artist in the creation of these works. How does the artist orchestrate these objects as art, or even as things worthy of contemplation?

Hetain Patel / at Chatterjee & Lal

published in Art India, April 2018, Volume 22 Issue 1

Hetain Patel’s video installations provoke Anuj Daga to think about performative worlds and their complex anxieties.

One notices the laborious pace of Hetain Patel’s quasi-photographic video work The Jump exhibited at Mumbai’s Chatterjee & Lal from February the 1st to March the 10th. Dressed as Spiderman, Patel stages a scene from the Hollywood film – he leaps like the superhero in his grandmother’s house as family members watch by in amazement. In the video of the jump stretched to about six minutes, projected in two settings back to back – one in the living room and the other against a neutral background – the act sets a strange dialogue between the wondrous and the absurd. As the viewer shuttles between two staged and carefully overlapping slow-motion videos installed back to back, the referentiality of the supernatural and the domestic begin to interchange. It is in the constructed lapse of time that one comes to terms with the spectacle of mundaneness as well as the ludicrousness of the spectacle.

Patel is a UK-based artist of Indian origin and his works explore these two worlds in close contact with each other. These works were recently also shown at Manchester Art Gallery. In a well-crafted performance that takes place between two individuals before their marriage alliance, Patel proposes a setting in which personal relationships get forged and the dance of life gets underway. Presented in order to question the boundaries of rituals, race, class, physical access and language, Don’t Look at the Finger opens up ways where bodies communicate and connect beyond words.

If only the story had not resolved itself neatly towards the end, it would have left the viewer moved and intrigued by its cinematic setting, pace and choreography. Patel makes the film accessible but also inaccessible – moves and gestures do not always add up predictably. Patel’s strategic experiment with narrative refers to Hollywood and some of its tropes but also destabilizes our expectations from time to time.

Tuesday, March 27, 2018

A Pritzker for India

Many think it's too late. Many also feel that the committee almost missed the opportunity of felicitating Charles Correa. And given the fact that both these architects - Charles Correa and B V Doshi have served the Pritzker committee for much time, it's hardly possible that they are unaware of their works, or their contribution. Much of the West, especially America remains obvilious of the architects from the South Asian subcontinent. When I was studying at Yale, many of my colleagues or professors had never heard of Charles Correa (who has his buildings in MIT campus in Boston, as well as in the city of New York). I wouldn't expect them to even know of B V Doshi either. India has, after all, never remained an interesting place to study contemporary architecture for the West. Rather, unfortunately, it still remains the land of the exotica - of "maharajas, elephants and snake-charmers" - as they popularly say. The West has always valued India merely for its rich past. My essay has this binary in the head, because it is indeed the way in which the West has categorically overlooked South Asia in both - historical or modern architectural scholarship.

I have plenty of anecdotes to prove the above slippage. I rather not get into it. Meanwhile, we all in India (must) agree that the Pritzker came to Doshi rather late. He's almost 90 years old, has not been actively building over the last decade, and has contributed significantly to the architectural discourse of India over the last 50 years. How do we reconcile this delay then? Doshi, as much as Correa, has always been a revered architect in India, and it would be incorrect to consider the Pritzker as a validation of his contribution. Infact, architects from the eastern "developing" countries have become Pritzker winners only in the recent past. Wang Shu was the first architect from China in the East to win a Pritzker in 2012, and now Doshi. For long, it has been the Aga Khan award that has held high regard in this region, one whose winners have maintained a low key, sustainable, egalitarian and humane architecture rather than the flamboyant, formalistic and high tech approach to buildings. It has been observed rightly, somewhere, that we see a trend in the Pritzker awards towards valuing a more humane Architecture in recent past. But is this "human" turn a mere tactic in foraying a more subtextual geopolitical move?

I have plenty of anecdotes to prove the above slippage. I rather not get into it. Meanwhile, we all in India (must) agree that the Pritzker came to Doshi rather late. He's almost 90 years old, has not been actively building over the last decade, and has contributed significantly to the architectural discourse of India over the last 50 years. How do we reconcile this delay then? Doshi, as much as Correa, has always been a revered architect in India, and it would be incorrect to consider the Pritzker as a validation of his contribution. Infact, architects from the eastern "developing" countries have become Pritzker winners only in the recent past. Wang Shu was the first architect from China in the East to win a Pritzker in 2012, and now Doshi. For long, it has been the Aga Khan award that has held high regard in this region, one whose winners have maintained a low key, sustainable, egalitarian and humane architecture rather than the flamboyant, formalistic and high tech approach to buildings. It has been observed rightly, somewhere, that we see a trend in the Pritzker awards towards valuing a more humane Architecture in recent past. But is this "human" turn a mere tactic in foraying a more subtextual geopolitical move?

Let us consider; if we may; the possibility of Doshi designing buildings outside India after his Pritzker status. Will the coming home of Pritzker bring Indian architects any desirability or attention in contributing to the world Architecture scene? At the most, like my colleague Prasad (Shetty) said over a conversation, an Indian Architect would be invited merely to build an Indian or Indian-looking building (embassies, Indian international centres, etc.) outside India. Never shall Indian architects have as much value as our longing for other Pritzker winners like Maki or Zaha (or even starchitects like Holl) would, to come and design for us. Largely, we have still remained underconfident and direction-seeking followers of the West. Our craving for validation from the West is undeniable. Yet, I don't disregard their superiority, for they have invested infrastructures and systems towards architectural scholarship and research. But how can we claim these for ourselves? In much regard, Doshi's constant recollection of Corbusier and the rhetoric of the "Indian" in his post-Pritzker acknowledgements almost works against claiming confidence in our contemporary modes of thought. We have forever been stuck in the identity question, to an extent that we seem to imagine ourselves incapable of articulating a world outside our own.

But supposedly, these are "Indian" values - precisely those that make us exotic and traditional. We can continue to celebrate these as the Pritzker finds place within India. The ideas of "modern", "Contemporary", "traditional" and so on require new articulation in our part of the world, specifically if we must come to value the architecture we produce. Such a revised framework for above terms is essential because we have not invested in institutions like museums or archives through which we can really assert a progression in thought. It is true that much of what we produce today is borrowed from floating imagery. But could we perhaps initiate a dialogue on the productive process (and even the creative effort) of constant hybridization that we constantly demonstrate in our built environment? Where else would you find so much experimentation? My claim may sound a bit shallow, but we do hope that in his acceptance speech, Mr. Doshi will lead us into a world where we come to sharply interrogate the existing notions of the above instrumental terms such as the "contemporary" or the "traditional" - amply explicated in his own work. It is thus, we may begin to claim some world architectural ground for ourselves.

Tuesday, March 20, 2018

MMRDA Entry Register

If you look closely, you will understand the inventiveness of this book. Expand the image and look at the first and last columns.

The above idea was put in place by the security staff of MMRDA (new block) so as to avoid the constant turning of the book in 180 degrees for taking details of the visitors.

Visitors notebooks have become a common place after the millennium in most public places as well as private housing complexes in cities of India, particularly Mumbai, as a manner of keeping tab on anyone who enters within their premises. Security guards are required to take the details of visitors that include their names, addresses, contact details and signatures. The entire affair is quite strange for over years, the act has almost become perfunctory. Both parties - the guard as well as the visitor is casual about the register, seen in the material condition of the book and the instruments (pen). No one knows who finally checks this data, and when? What happens of these countless pages of information at the end of the book? If one sits with these registers after their completion, they could provide us an interesting geography of visitors to a single place - the flows of people and objects precisely.

This is indeed a valuable cultural product - one that indexes the manifest of (in)securities arising due to certain events in a certain time in history in urban areas, taking a unique form along with its assisting infrastructure of security scanners (in public places) and acts of body-frisking!

In an age where rubberband and paperclip are personalising the object of a note book, how does one think of book as a communal entity within which several people write at once? In the above case, for example, the book is filled in by numerous individuals, from different directions and multiple handwritings. It is these engagements in space and time that give the book its ultimate form. The above example is exceptional as it helps opening up so many dimensions of use, regulation, aesthetic, record keeping, sharing, space - and so on. The construction of the register is simultaneously regarded and disregarded.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)